The five-year survival rate for people on dialysis is under 50 percent. University of California researchers are hoping to improve that prognosis.

When kidneys fail, the body is unable to rid itself of toxins, waste products, and excessive fluids. Dialysis or transplants are the only treatments for the 786,000 people in the U.S. whose kidneys are in the final stage of failure, called End Stage Renal Disease.

Transplants are difficult to get, with nearly five times as many patients on a waiting list than the number of donor organs available. Unfortunately, the mortality risk for dialysis patients is also high, even compared to the risks for cancer and other diseases.

A new $3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health will allow statisticians at UC Riverside, UC Irvine, and UCLA to better understand and mitigate the factors causing these patients to die.

“There are roughly 6,000 dialysis facilities across the US, which amounts to a huge number of people facing very uncertain outcomes,” said UC Riverside statistician Esra Kurum, a co-principal investigator of the project. “If we can increase their rates of survival, it will be a huge service to these patients.”

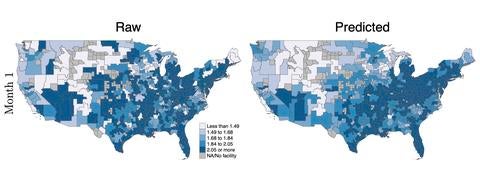

Statisticians typically begin with a single-level analysis, meaning everyone in a given population is lumped into a single data set, Kurum explained. For this project, she and her colleagues will develop new analysis models to reach a more nuanced understanding.

The models will account for patient, facility, and regional factors. These include staffing levels at different dialysis facilities, periods in which patients are most at risk of dying after starting dialysis, and how other medical conditions might complicate outcomes.

“Dialysis patients often have other co-morbidities, including depression, cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases,” Kurum said. “We want to identify the effects of these other risk factors.”

Data for the project is coming from the U.S. Renal Data System, which collects and distributes information about nearly all dialysis facilities in the country. Data shows the nation’s minority and low-income patients are disproportionately affected by renal disease, and that gender also accounts for some differences in outcomes.

“With a data set this broad, we’ll be able to provide a basis for helping these populations more specifically,” Kurum said. “We’re no longer just saying, ‘If you’re female, your risk is always 10% more.’ Outcomes can change over time and depending on where in the country you are.”