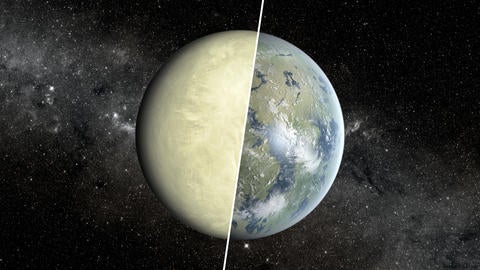

By joining NASA on its newly announced missions, UC Riverside is hoping to learn how Venus went from pleasant, Earth-like planet to blistering wasteland.

The twin missions mark the first time in more than 30 years the agency has ventured to Earth’s closest planetary neighbor. NASA also considered missions to Jupiter and Neptune, but ultimately chose these two based on their potential scientific value and feasibility of their development plans.

UCR astrobiologist Stephen Kane, who helped devise those plans, is thrilled by the selection.

“This is long overdue because we know so little about Venus,” said Kane. “It’s possible that Venus is a preview of what Earth could eventually look like.”

These projects represent UCR’s first time being involved in planetary missions. NASA is awarding approximately $500 million per mission for development. Each is expected to launch between 2028 and 2030.

Kane is on the science team for the DAVINCI+ mission, which will probe the acid-filled Venusian atmosphere to measure noble gases and other chemical elements. He also collaborates with the VERITAS mission, led by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. That mission will allow scientists to create 3D reconstructions of the landscape, revealing whether the planet has active plate tectonics or volcanoes.

“Earth’s plate tectonics and liquid water oceans allow it to recycle carbon from the atmosphere into the planet’s interior, and Venus doesn’t have either of those anymore,” said Kane. “We need to understand the processes that caused it to change.”

Along with Colby Ostberg, a UCR doctoral student in planetary science, Kane will look for proof that Venus once had liquid water on its surface, a key marker of habitability. They will also try to understand the evolutionary pathway that led Earth’s “evil twin” to become the hottest planet in the solar system, with surface temperatures of more than 800 degrees Fahrenheit.

“Given that Venus is the most similar planet to Earth in the solar system in terms of size and mass, one has to wonder why its climate is so dramatically different,” Ostberg said. “These missions will help answer this question, and lead to a better understanding of rocky planet evolution.”

A runaway greenhouse environment boiled any liquid oceans Venus may once have had, baked its surface, and made the planet uninhabitable for life as we know it. “It’s not clear that being closer to the sun was the primary cause of the intemperate environment,” Kane said. “Mercury is even closer but Venus is hotter.”

Kane’s previous research determined that Jupiter may have played a role in altering the orbit of Venus, and as a result, its evolution. He now hopes to extend insights on planetary habitability gleaned from the new Venus missions to planets around other stars.

“I look for Venus analogs, and the only way we’ll understand them is by having deeper insights into our sibling planet,” he said.