New UC Riverside research shows fungi and bacteria able to survive redwood tanoak forest megafires are microbial “cousins” that often increase in abundance after feeling the flames.

Fires of unprecedented size and intensity, called megafires, are becoming increasingly common. In the West, climate change is causing rising temperatures and earlier snow melt, extending the dry season when forests are most vulnerable to burning.

Though some ecosystems are adapted for less intense fires, little is known about how plants or their associated soil microbiomes respond to megafires, particularly in California’s charismatic redwood tanoak forests.

“It’s not likely plants can recover from megafires without beneficial fungi that supply roots with nutrients, or bacteria that transform extra carbon and nitrogen in post-fire soil,” said Sydney Glassman, UCR mycologist and lead study author. “Understanding the microbes is key to any restoration effort.”

The UCR team is contributing to this understanding with a paper in the journal Molecular Ecology.

In addition to examining megafire effects on redwood tanoak forest microbes, the study is unusual for another reason. Soil samples were pulled from the same plots of land both before and immediately after the 2016 Soberanes fire in Monterey County.

“To get this kind of data, a researcher would almost have to burn the plot themselves. It’s so tough to predict exactly where there will be a burn,” Glassman said.

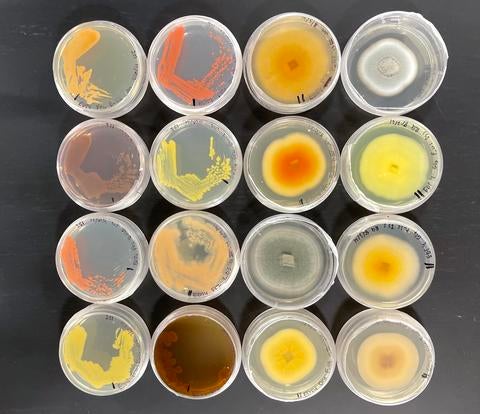

The team was not surprised to find that the Soberanes fire had a massive impact on bacterial and fungal communities, with as much as a 70% decline in the number of microbe species. They were surprised that some yeast and bacteria not only survived the fire but increased in abundance.

Bacteria that increased included Actinobacteria, which are responsible for helping plant material decompose. The team also found an increase in Firmicutes, known for promoting plant growth, helping control plant pathogens, and remediating heavy metals in soil.

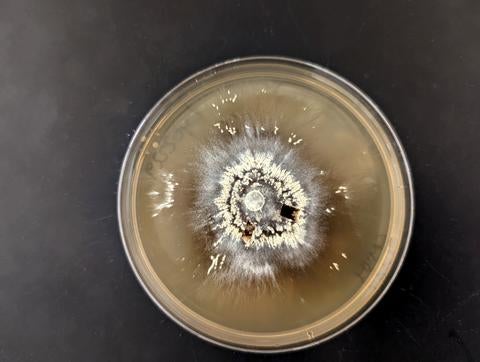

In the fungal category, the team found a massive increase in heat resistant Basidioascus yeast, which is able to degrade different components in wood, including lignin, the tough part of plant cell walls that gives them structure and protects them from insect attacks.

Some of the microbes may have used novel strategies for increasing their numbers in the burn-scarred soils. “Penicillium is probably taking advantage of food released from necromass, or ‘dead bodies,’ and some species may also be able to eat charcoal,” Glassman said.

Perhaps the team’s most significant finding is that fungi and bacteria — both those that survived the megafire and those that didn’t — appear to be genetically related to one another.

“They have shared adaptive traits that allow them to respond to fire, and this improves our ability to predict which microbes will respond, either positively or negatively, to events like these,” Glassman said.

In general, little is known about fungi and the full extent of their effects on the environment. It is imperative that studies like these continue to reveal the ways they can help the environment recover from fires.

“One of the reasons there is so little understanding of fungi is that there are so few mycologists who study them,” Glassman said. “But they really do have important impacts, especially in the aftermath of major fires which are only increasing in frequency and severity both here and across the globe.”